Futuredays illustrates the great expectations for the year 2000 entertained by Jean-Marc Coté and his fellow artists more than a century ago.

Starting in 1899, a commercial artist named Jean-Marc Côté and other artists were hired by a toy or cigarette manufacturer to create a series of picture cards as inserts, according to Matt Noval who writes for the Smithsonian magazine. The images were to depict how life in France would look in a century’s time, no doubt heavily influenced by Verne’s writings. Sadly, they were never actually distributed. However, the only known set of cards to exist was discovered by Isaac Asimov, who wrote a book in 1986 called “Futuredays” in which he presented the illustrations with commentary.

The possibilities of science must have seemed endless, and technologies that would fundamentally change society would seem all but likely, as in one illustration that shows books being ground up and fed directly into the ears of schoolchildren. While it may seem a bit to Matrix-like to become a reality, one could argue that this is fundamentally what an audiobook is or what the Internet does with information. We may not be at the point where information is fed directly into our brains, but reality isn’t that far off.

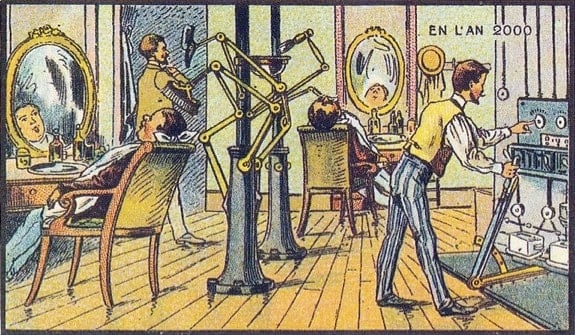

In light of the Industrial Revolution in France in the early part of the 19th century, automation would have been rife with possibilities. Among the collection, personal automatons — or robots as we call them — showed up prominently. Clearly, the artists felt they would be a big part of the future, taking care of many of the mechanical tasks used in daily life, such as robot barbers.

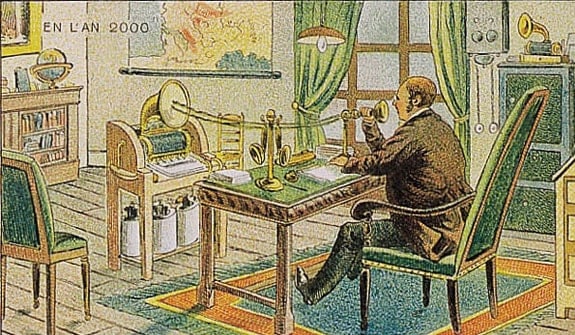

Initial technological strides made in electromagnetism and wireless communication led to the invention of the telephone and radio during the latter decades of the 19th century. To the artists, it seemed certain that these technologies would play an important part in the future, so a machine was imagined that would transcribe spoken language into print, something that the automated audio transcription services or voice recognition services of today now make possible.

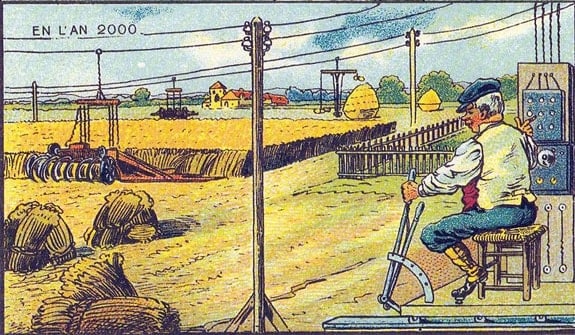

The artists also imagined how robots would have an even bigger impact on society, as in helping farmers plow fields. Robots on farms are on the rise, as bots have been developed to milk cows, pick only ripe strawberries, and even kill weeds.

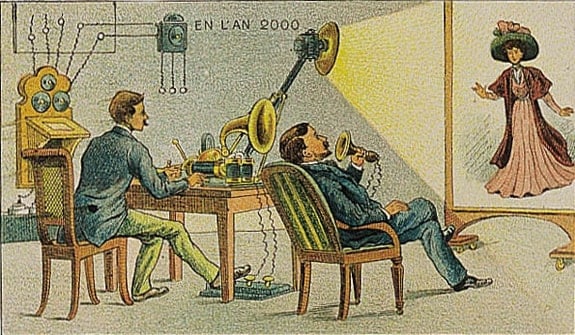

Another card shows video calls imagined from the technology of the day (a projector), but functionally the same as Apple’s FaceTime, Google Hangout, or any other standard video conferencing software.

Another card shows video calls imagined from the technology of the day (a projector), but functionally the same as Apple’s FaceTime, Google Hangout, or any other standard video conferencing software.

The artists were fascinated by the possibilities of flight. This makes sense, considering that powered gliders were in development during the 1890s, the first Zeppelin was being constructed in 1900, and the Wright brothers made their historic flight in 1903. But personal flight was envisioned to be much more integrated into daily life, envisioning that wings would help people do all sorts of things like delivering mail…physics be damned!

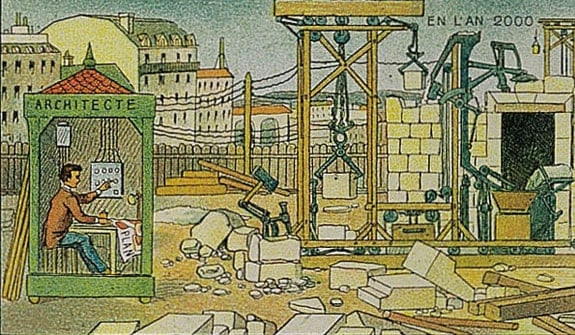

But the scope of using machines to do work wasn’t seen to be limited to smaller scale activities. Why not use machines to allow a single person to construct buildings? We aren’t there yet, but recent advances in 3D printing almost beg for houses and other buildings to be printed out, if the technology could be worked out.

Other types of advances in projection were expected as well, allowing microscope or telescope images to be much more visible. While projection technologies like these were developed, today digital instruments and monitors are the workhorses for microscopy.

Imagining the future is vital to progress, as it means technological advances are the result of deliberate efforts to make ideas reality, rather than simply humans reacting to their surroundings like animals. These illustrations are a testament to a handful of very creative artists who tried to bring a vision of the future to the masses. How unfortunate that the people of the time never got to seem them.